World of Wonder

The Age of Enlightenment filled the minds of men and women with wonder. It was a period of observation and discovery. Books furnished an avid public with new knowledge of the earth and the heavens. Information was presented in novel ways to captivate and educate the reader. These books inspire and delight. Geometric forms rise up out of the page, the moon spins on a turning wheel, and the invisible is rendered visible.

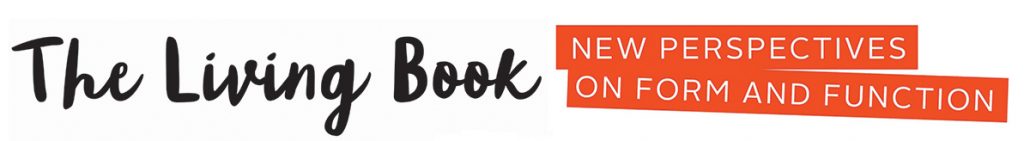

John Seller, Atlas Coelestis (London, 1677).

This celestial atlas is full of plates that are folded and bound into this little book to use under the starry skies.

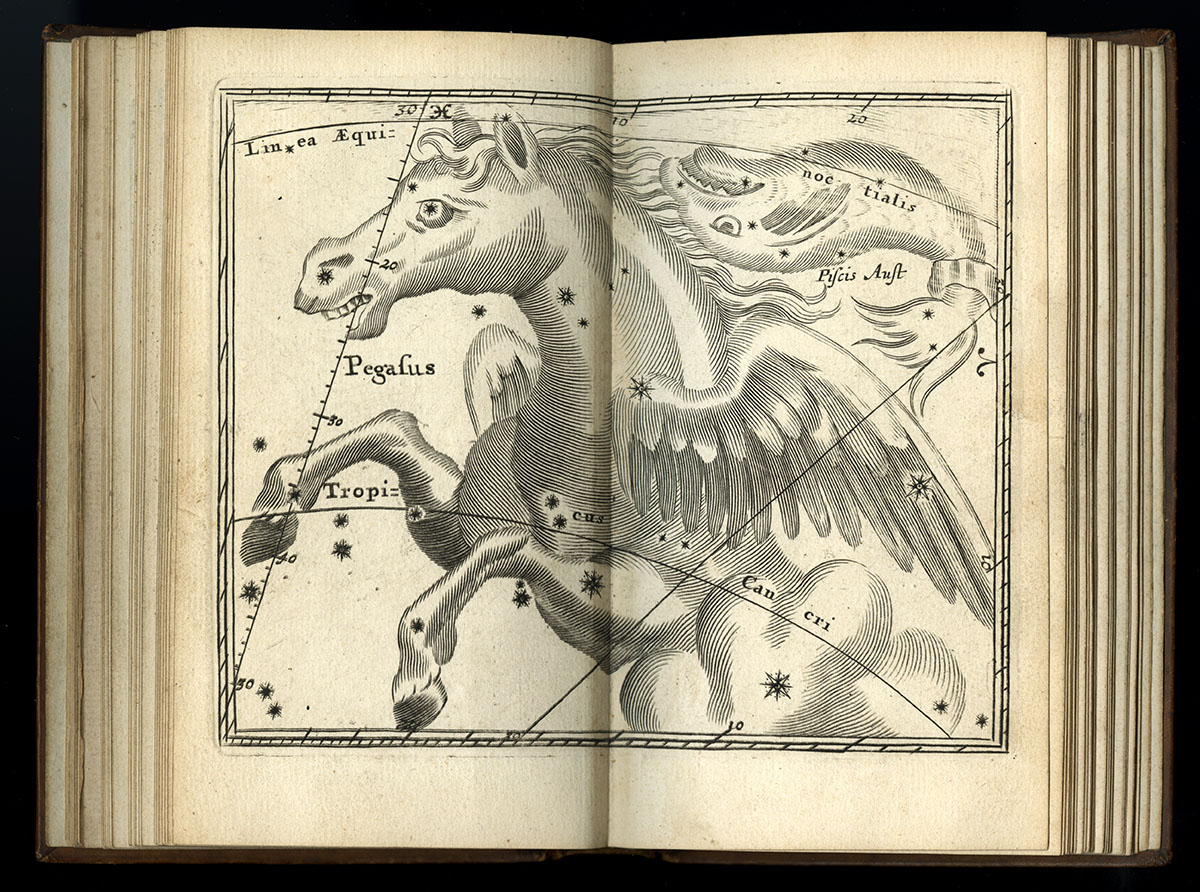

John Lodge Cowley, An Illustration and Mensuration of Solid Geometry in Seven Books (London, 1787).

This entire book is made up of plates that fold up into different geometric forms.

See Video on Home Page

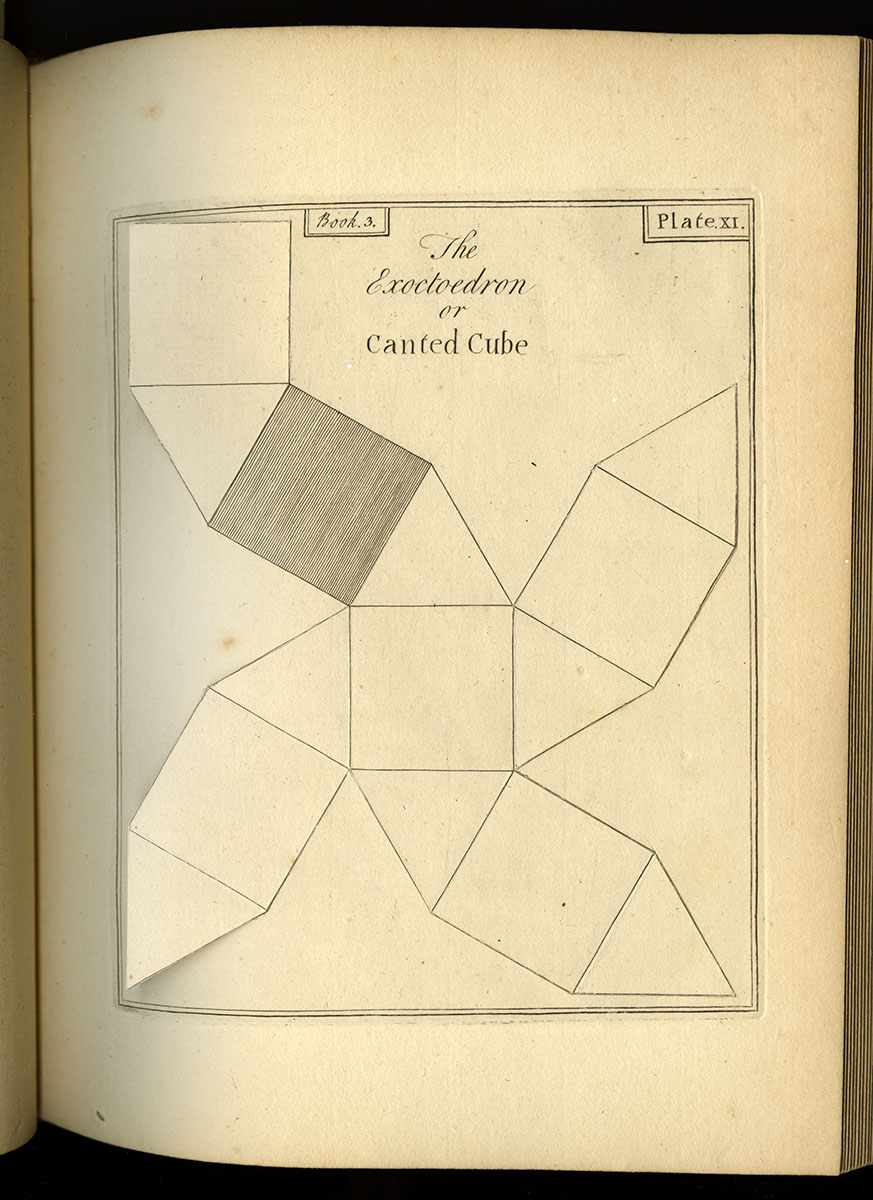

George Poulett Scrope, Memoir on the Geology of Central France (London, 1827).

Scrope showed how volcanic action is part of earth’s history. This long accordion panorama echoes the geologic forms that it illustrates.

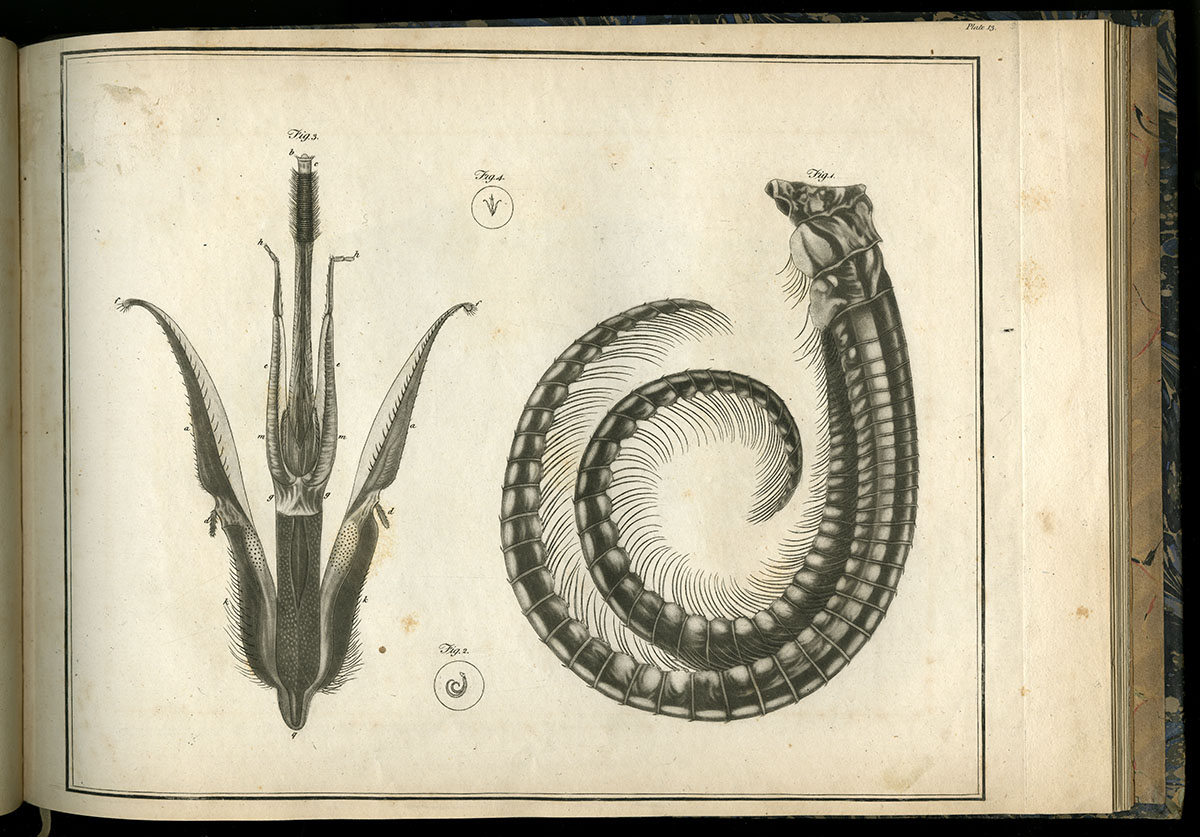

George Adams, Plates for the Essays on the Microscope (London, 1787).

Adams, a British instrument maker and optician, sold this book of plates, along with his telescopes, in his shop. Note the tiny circles, figure 2 and figure 4, which show the actual size of a bee’s proboscis.

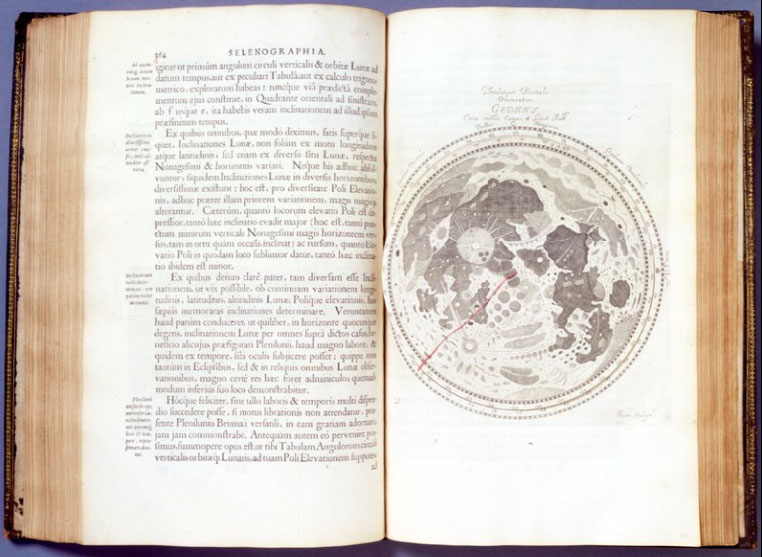

Johannes Hevelius, Selenographia (Gdansk, Poland, 1647).

Hevelius devoted himself to studying astronomy and built an observatory in his house. He engraved all the plates for this book himself and created this volvelle to show the waxing and waning of the moon.

Carl von Linné, Fundamenta Botanica et Systema Naturae (Lucca, Italy, 1758).

The illustration in this book titled “Amor unit Plantas” (love unites the plants) conveniently folds out of the back for easy access. Linnaeus introduced a classification system for plants based on sexual reproduction.

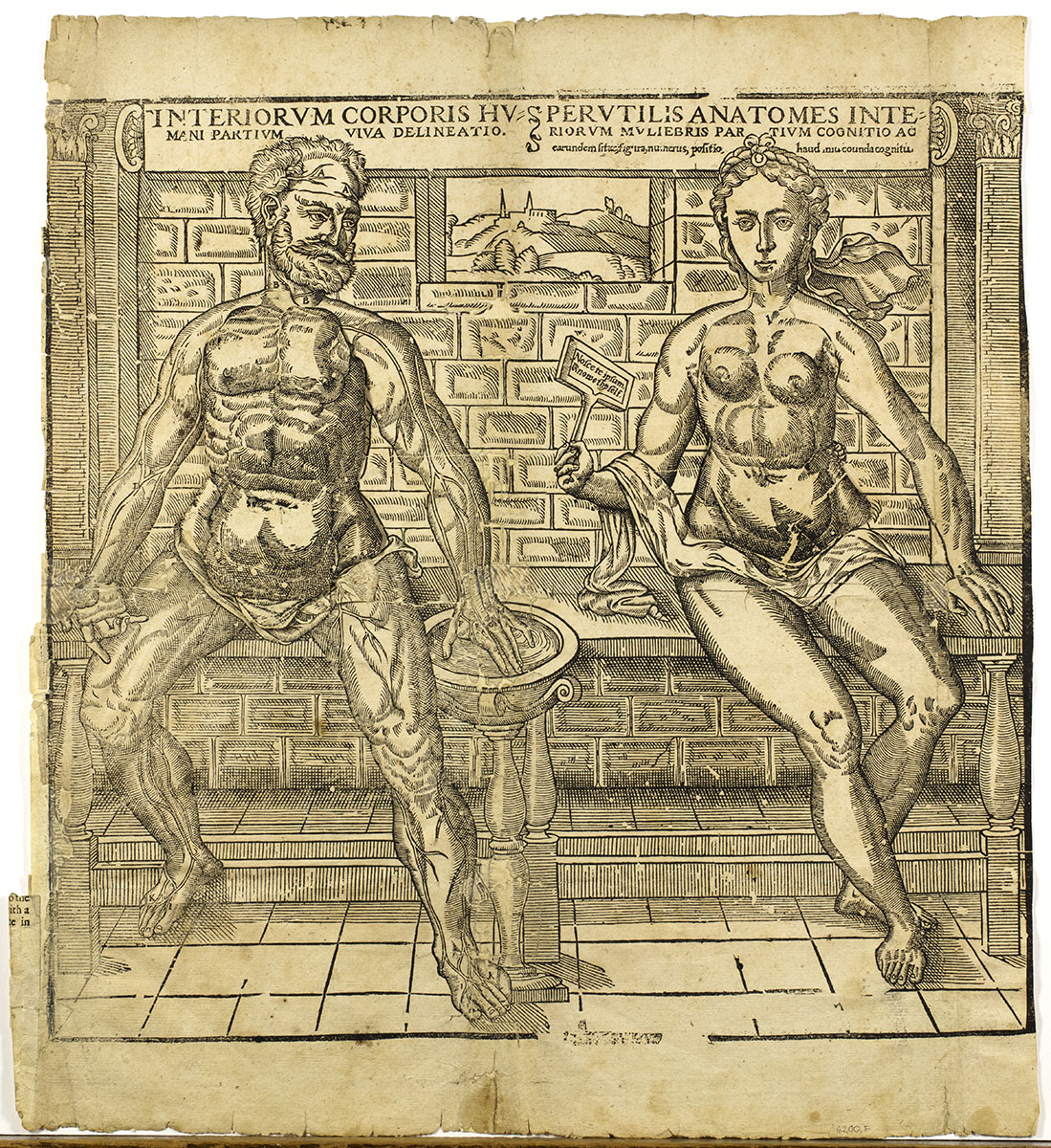

Anatomy of the Inward Parts of Woman (London, 1650).

This page, and not the book where it once lived, is all that exists in the Library Company’s collection. In anatomical books, flaps were often used to show the inner parts of the body.

See Video on Home Page

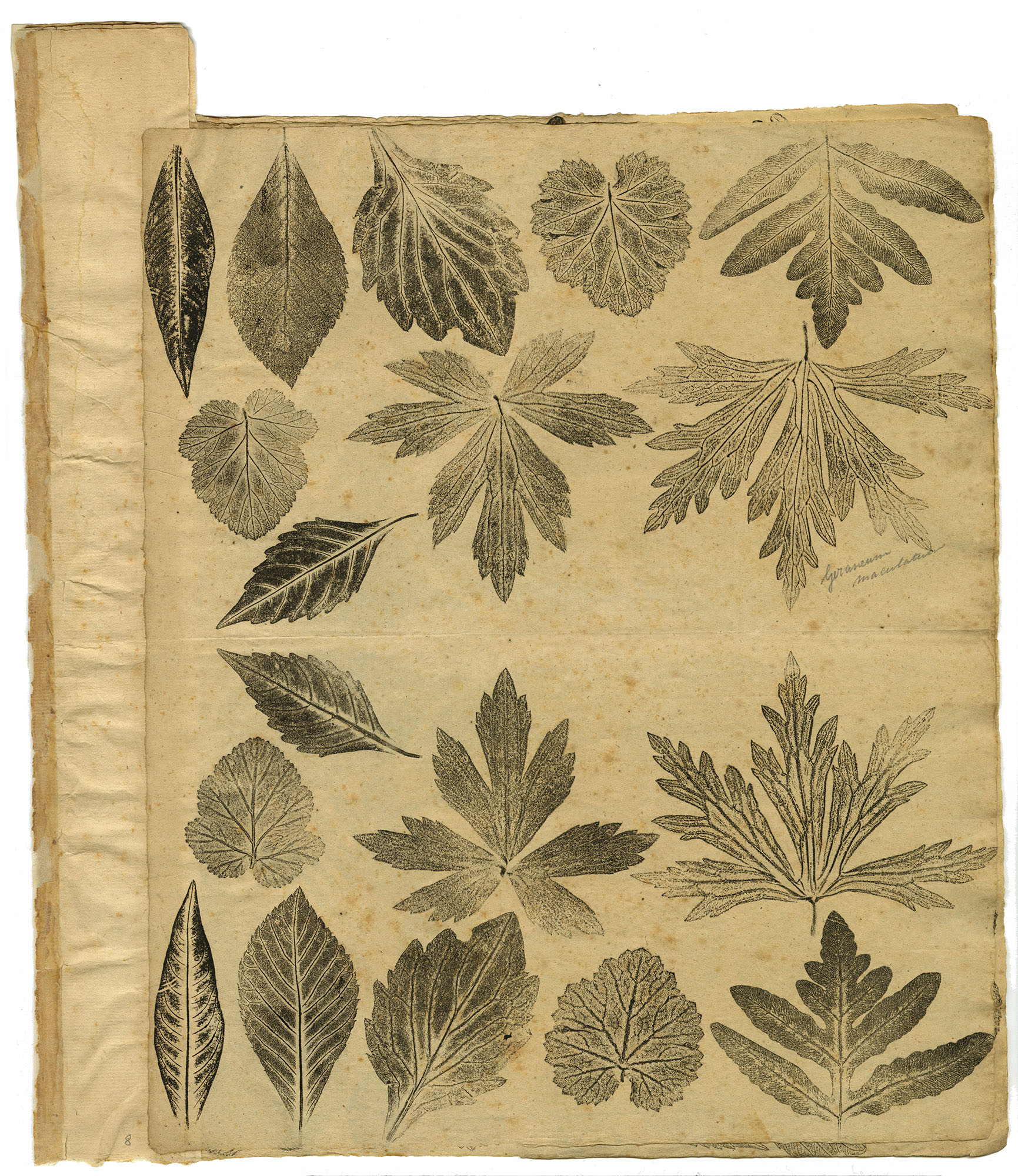

Joseph Breintnall’s leaf prints (Philadelphia, ca.1731- ca. 1742).

The vertical fold in the page is a clue as to how Brientnall achieved these detailed leaf impressions. He inked the leaf, folded the paper over the leaf and then used pressure to create the print. He made hundreds of leaf prints like this to collect botanical information. The tab on this page is evidence that this was bound in a book.

Cephas Grier Childs, lithographer after John James Audubon, Rallus Crepitans. Marsh Hen (Philadelphia: Childs & Inman,1832). Lithograph.

Some Audubon prints this large were published in a book format called elephant folio.